SPIRIT OF STANLY: What’s in a name? Quite a bit for Stanly County residents

Published 11:42 am Monday, April 4, 2022

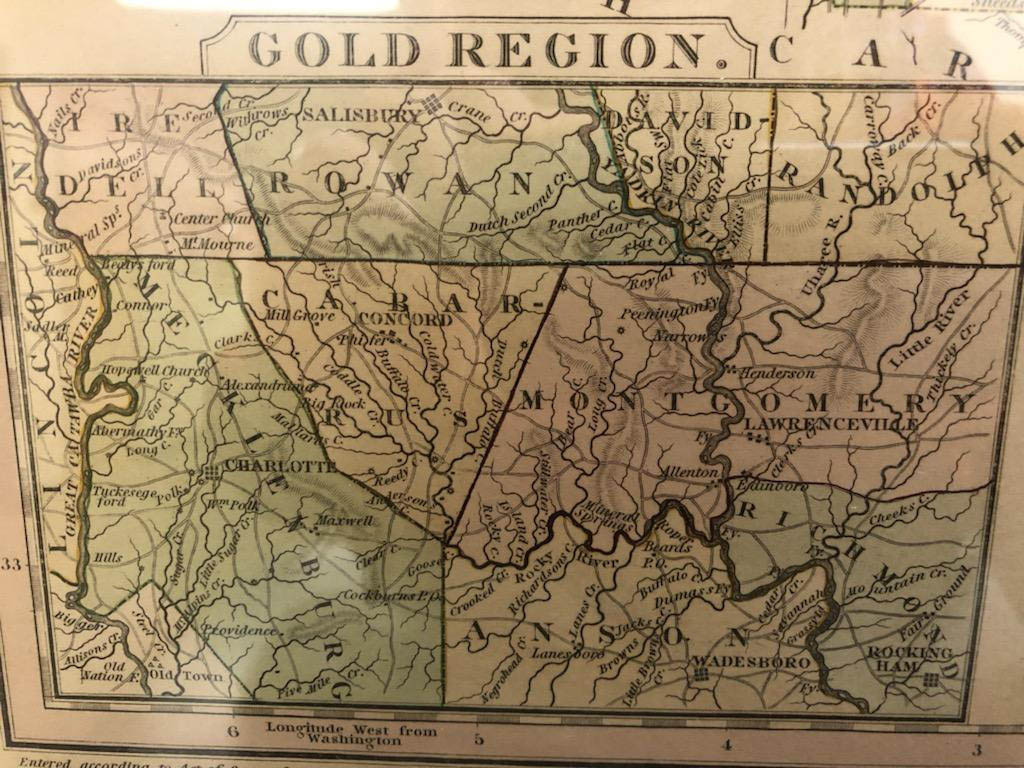

- This map shows what the area looked like when Stanly County was part of Montgomery County. (Contributed)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(Editor’s Note: This is one of several stories featured in the March 27, 2022, issue of The Stanly News & Press, which featured a special section called Spirit of Stanly.)

Throughout the course of its history, Stanly County has often been spelled incorrectly, usually with people inserting an “e.” Many likely have confused the county with the small town of Stanley in Gaston County.

The incidents caused so much consternation for the community that in 1971, then-N.C. Rep. Lane Brown passed legislation changing the spelling of the word “Stanley” to “Stanly” in all acts referring to the county.

Trending

But just how did the county come by its unique name?

The official origins of the county date back to 1841, when Stanly County was formed from the part of Montgomery County west of the Pee Dee River. The county was named after politician John Stanly, even though Stanly never set foot in the area.

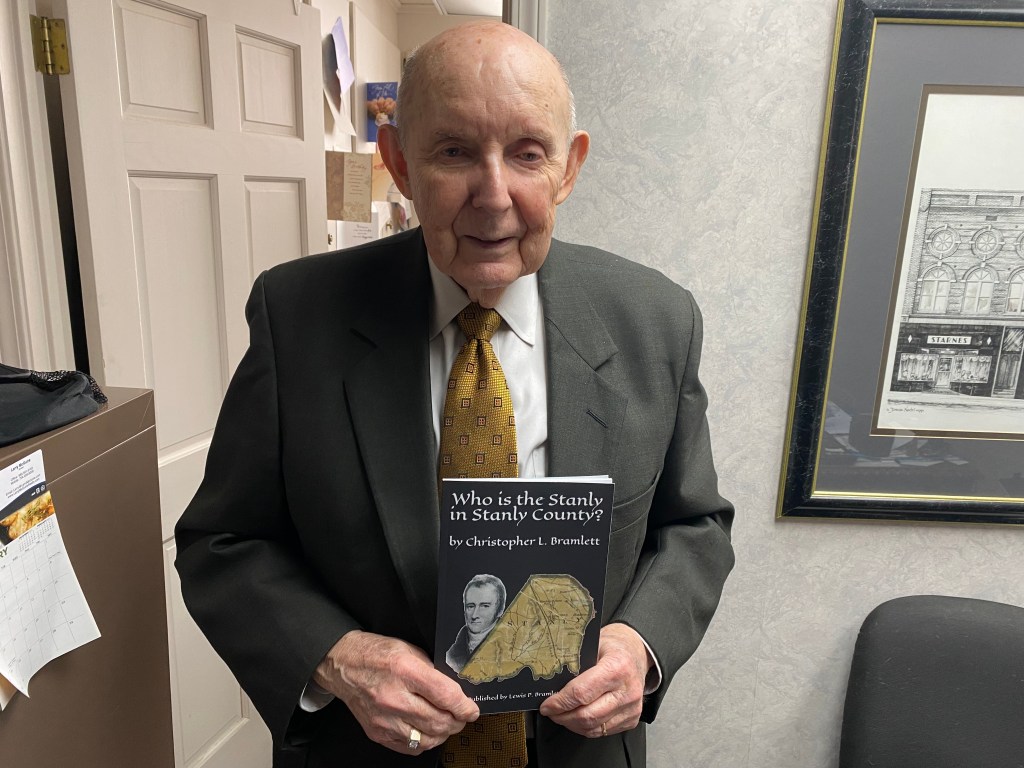

Aside from having the same name, “John Stanly had no connection with Stanly County whatsoever,” according to Chris Bramlett, who wrote a book two years ago about the subject titled “Who is the Stanly in Stanly County?” He’s enjoyed learning about the historical figure ever since he portrayed John Stanly for a series of events during the county’s 150th anniversary several years ago.

Bramlett estimates the name “Stanly” was likely chosen as a way of ensuring the county would get approval from the state legislature in Raleigh.

But how did John Stanly, arguably one of the more color characters in North Carolina’s early history, attain such prominence that even after his death, one of the state’s 100 counties took his name?

Stanly was born in 1774 in New Bern, North Carolina to prominent businessman and Revolutionary War hero John Wright Stanly. According to Bramlett’s research, there is a strong likelihood that the family descended from the Stanleys in England, and that at some point in his life, John Wright Stanly, who was most likely born John Stanley, dropped the “e” and added the middle name to differentiate himself from his English ancestors.

Chris Bramlett wrote a book which included information on John Stanly, for whom Stanly County is named. (Contributed)

Trending

Bramlett found that another possible explanation for why John Wright Stanly dropped the “e” in his last name came from a trip he took to India during the Revolutionary War. He met a soldier by the name of Stanley and upon learning they had the same last name, the British soldier suggested they were related. John Wright Stanly did not like this and asked the man how he spelled his last name. The soldier spelled it with an “e,” to which point, according to Bramlett’s book, Wright Stanly replied, “Oh, then we can’t be kin because my name is spelled S-t-a-n-l-y.”

Unlike his father, who made a name for himself in the shipping business and had a propensity for gambling, which got him repeatedly into trouble, John Stanly graduated from Princeton University and spent his career practicing law. As an ardent member of the Federalist Party, which valued a strong national government and was the country’s first official political party, he also secured for himself a successful political career, serving two terms in Congress and several in the North Carolina House of Commons. He also served a stint as N.C. Speaker of the House.

The house where Stanly grew up, known today as the John Wright Stanly House, has been called one of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in the South. President George Washington spent two nights at the home in 1791 and it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Stanly had such a sharp legal mind that during his time in Washington, D.C., per Bramlett’s book, Daniel Webster, a congressman who later served as U.S. Secretary of State for multiple presidents, introduced him to Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall with the following compliment: “As a lawyer he is your equal and my superior.”

Despite his rise to prominence in state and national politics, Stanly had a nasty temper, Bramlett wrote, and he made some enemies, most notably Richard Dobbs Spaight, the eighth governor of North Carolina, and a signer of the U.S. Constitution who had represented the state in both the Continental Congress and the United States Congress. Though originally a Federalist himself, Spaight’s increasing concern with states’ rights led him to abandon the party and join the Democratic-Republican party.

A bitter political argument between the two men developed during the early 1800s and it became so untenable that they decided to resolve their issues the way many men did during that era: by engaging in a duel.

On Sept. 5, 1802, the two men met behind Masonic Hall in New Bern. Gunfire was exchanged three times, but neither man was hurt. On the fourth attempt, Stanly hit Spaight in the side and he died the next day.

Despite the public outcry, Gov. Benjamin Williams pardoned Stanly for the act, which became the last duel in the state, as in November the General Assembly passed a law entitled “An Act to Prevent the Vile Practice of Dueling Within This State.” If someone did participate in another duel, they would be heavily fined and barred from public office; in addition, the survivor of such an exchange would be hanged “without the benefit of clergy.”

The duel didn’t seem to tarnish Stanly’s reputation as many of his years serving in Congress and the House of Commons occurred after that fateful day in New Bern.

While serving as Speaker of the House in 1827, Stanly suffered a debilitating stroke and was never the same. He died in 1833 at the age of 59 and was buried in his hometown of New Bern.