A look at the front lines of the opioid battle

Published 3:28 pm Monday, December 23, 2019

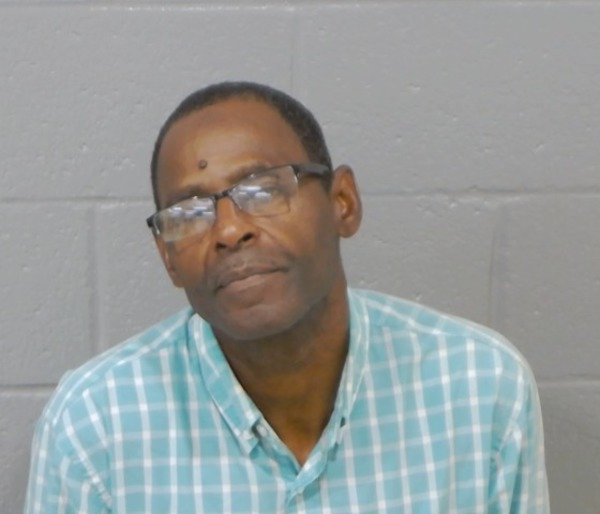

- Stanly community paramedic Mike Campbell unloads one of the EMS gurneys.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Stanly County’s opioid epidemic, the paramedics are on the front lines. They are the ones that respond to overdose calls, often administering Narcan, a medication that reverses overdoses and helps save lives.

While paramedics traditionally respond to 911 calls for emergency medical assistance, which can mean a whole host of different issues, over the past few months, a new program was created in Stanly to specifically target people suffering from opioid overdoses.

The community paramedic program was established in May and currently consists of three paramedics whose job is to respond to opioid overdose calls.

Trending

Mike Campbell is one of the paramedics.

During a recent ride-along, The Stanly News & Press talked with Campbell about topics such as ways to alleviate the stigma of addiction, how paramedics deal with post-traumatic stress disorder and how a community effort is needed to combat the opioid epidemic.

Origins of the program

The program is geared toward primarily responding to opioid overdoses. The program’s narrow focus makes it unique in the state. Campbell said there are only a few other EMS agencies, such as ones in Onslow and Halifax counties, that have similar programs.

The program was created to curb the rising opioid overdose numbers in the county. EMS Manager Mike Smith helped design the program, which was based on his experience with a similar program in Cabarrus.

With the support of a two-year, $400,000 Blue Cross Blue Shield grant the department received this year, the program began in May.

Trending

Campbell, 35, applied for the program late last year.

“I liked the concept of it,” he said, “and I liked the idea of being able to help people in a different way than EMS typically does. I knew it was going to be a challenge and I like a challenge.”

Originally from Mooresville, where he still resides with his wife and two daughters, Campbell spent about a decade in Charlotte working for Mecklenburg County EMS before transitioning to Stanly EMS, where he has worked since July 2018. Having a father who was a physician and a mother who is a nurse, “I’ve always wanted to be in the health care-type setting one way or another,” he said.

Stanly community paramedic Mike Campbell. (Picture provided by Mike Campbell)

Campbell had a personal connection that made him want to join the program. His sister has been struggling with addiction and mental health issues for around 20 years. He has seen the toll its taken on his family.

“I’ve witnessed it firsthand and what it’s done to our family and I want to prevent that from happening to other people’s families,” he said.

Campbell said each day as a community paramedic is different. Some days may feature the paramedics responding to as many as four or five overdose calls while other days there may be none.

He and the other paramedics rotate between working three and four days a week from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The schedule allows him time to spend with his family.

During the ride-along, the only call Campbell responded to wasn’t related to an overdose. He traveled to the Albemarle Correctional Institute to help an inmate who was having chest pains.

Campbell said paramedics usually receive a higher number of overdose calls at the beginning of each month. Though he is not sure why, he said Stanly EMS is looking into research to determine a reason.

“If we could figure it out we could probably work with the health department or some other agencies to try and prevent that from happening,” Campbell said.

The community paramedic program was primarily created to prevent the death of people, often young people.

“We want the citizens here to live full, productive lives and we want to connect people with options to make that possible for everybody,” he said.

Numbers don’t lie

The amount of opioid overdoses — and subsequent lives lost — in the county does merit it being referred to as a crisis, Campbell said.

The data certainly backs it up.

Stanly has consistently ranked No. 1 in the state for the rate of opioid overdoses resulting in hospital visits over the past year, according to data from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services. After the county dropped out of the top 10 in September, Stanly reclaimed the No. 1 spot for October, before again dropping out of the top 10 for November.

From January to November, the county has had 92 opioid overdose emergency room visits, according to the data, much less than the 124 during the same time period last year. The busiest month so far has been May, which featured 15 hospital visits.

But the state’s numbers only tell part of the story since many people who overdose decide not to go to the hospital.

According to EMS data provided by Campbell, which tracked the number of overdose calls from May through the end of September, the community paramedics responded to 157 calls.

Of the calls, 64 percent were for male patients while 35 percent were for people ages 26 to 35. The patients were overwhelmingly white (87 percent) and the majority overdosed on opiates (62 percent).

Once Narcan was administered, 53 percent of patients were transported to the emergency room, while 43 percent refused transport.

On the scene

The community paramedic’s role when they get dispatched is to support the traditional EMS crew until the patient is stabilized. But their work doesn’t stop after the patient is taken to the hospital.

After the patients are administered Narcan, the community paramedics spend at least an hour talking with them to learn more about their overdose history and their willingness to enter into a treatment program. They also issue Narcan kits to patients and their families and teach them how to properly administer the medication.

The conversations are never judgmental, Campbell said. The paramedics are simply trying to learn about the patients to be able to help them in the best way possible.

“We try to be friendly with them, we try to be empathetic toward them,” Campbell said.

An important part of the paramedic’s job is to make it easy for patients to find treatment options.

“We follow up with them and we try to get them somewhere to where they can receive help that they’re not getting right now,” Campbell said.

The help comes from Monarch’s behavioral health clinic in Albemarle, detox centers around the area and other treatment facilities.

Campbell said patients who want help will be honest with the paramedics and talk about why they started taking drugs and why it is hard to maintain sobriety.

Paramedics will also call patients to follow up and make sure they are okay. The paramedics are there to provide support if the patients need anything.

Campbell said the most rewarding aspect of the job is helping others.

“It makes me feel good to know that somebody is better now than before they called me and we made a difference in that person’s life,” he said.

Combating stigma and stereotypes

While opioids are not naturally bad, they are addictive, Campbell said. Many people become hooked after being prescribed opioids due to an injury.

Campbell said people often think they do not deserve help because they are too worried or embarrassed about how others will view them or they think they will be treated differently. So instead of reaching out, people fall back into their addiction.

One of the biggest challenges for paramedics is talking patients into believing they deserve treatment.

“We’re trying to change that (addiction) on all ends of the spectrum and remove the stigma from that,” he said, “because if someone needs help they need help and as a community, we shouldn’t be judgmental over why or how they need help.”

Campbell said some people are distrustful of paramedics because they believe they will report their substance abuse to police or social services. Part of the paramedic’s job is to reassure patients that their personal information will not be sent to other agencies.

Dealing with the stresses of the job

Being a first responder is a stressful and pressure-filled job, with many professionals routinely encountering tragedy and death.

But Campbell is up to the task.

“I like the pressure of it,” Campbell said.

Because the job is inherently stressful, Campbell said he tries to separate his work from his personal life as much as possible, through fishing and camping with his family on vacation.

He also has people — including his friend and former partner Eric, who works for Mecklenburg EMS, and his friend Nick, who’s a firefighter in Mooresville — who he can talk to about anything related to the rigors of the job.

“We can all call each other at any time of day and any time of night,” Campbell said.

Many first responders struggle with coming to terms with the death and tragedies they encounter on a regular basis, with many of them suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder or depression.

Stanly EMS recently created a critical incident stress team to focus on the mental health of first responders. The team is available to talk to first responders who might be struggling.

“We know that we can’t take care of other people if we can’t take care of ourselves,” Campbell said.

Campbell said first responders often turn to substances to cope with some of the grim realities of the job. This can lead to substance abuse and potentially suicide.

“One suicide from a first responder is one too many,” he said.

Campbell has known first responders who have struggled with substance abuse.

“It happens everywhere,” he said. “It doesn’t discriminate against who you are or what you do for a living.”

It takes a village

The community paramedics are not alone in the fight to help those suffering from opioid addiction.

Aside from Stanly EMS, other local resources include Monarch, Will’s Place, Stanly County Health Department, Daymark Recovery Services, 33 Recovery, Bridge to Recovery, Esther House, Safer Communities Ministries and Cardinal Innovations.

Several of the paramedics are part of Project Lazarus, a local group comprised of public health, health care, law enforcement, mental health personnel and concerned citizens to combat drug abuse.

“We’re working with the rest of the community to fight an epidemic that we’ve been losing for a long, long time,” Campbell said.

He hopes the community paramedic program grows and eventually helps Stanly to remain outside the top 10 in the state in opioid overdoses.

“But in order for that to be successful, the community needs to come together,” he said.