Suicide whips up a different kind of storm

Published 3:05 pm Monday, September 24, 2018

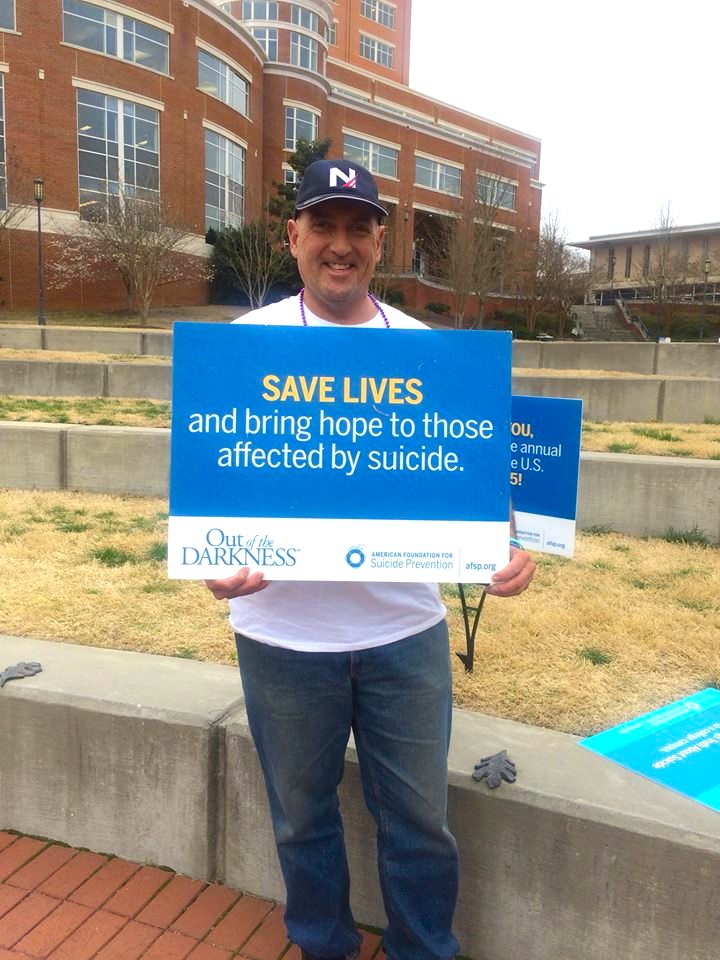

- APD officer Lance Fallen at an Out of Darkness Walk at UNC Charlotte. Fallen is now teaching suicide awareness courses in Stanly County in memory of his lost friend Lauren.

The suicide of his best friend hit Lance Fallen as hard as a hurricane. All the flurry and devastation of a storm, but with none of the warning.

“One day she was there and the next she was gone,” said Fallen, an officer for the Albemarle Police Department. “I never saw it coming.”

The sudden squall that swept his friend Lauren away occurred on April 3, 2017. She was 25 and the mother of three.

Trending

“She was the best kind of friend you could ask for,” Fallen said. “She was fun, a great personality, a great person to hang out with, a great mom, a great daughter.”

But like most storms, suicide doesn’t discriminate. It devastates all. And Fallen isn’t the only one in Stanly who has learned that lesson the hard way.

According to the latest data, the county ranks 18th in the state for suicide rates. From 2012-2016, the health department recorded 47 such deaths, an average of 11 per year. Of those, 22 were ages 40-64, 22 were ages 20-39, and three were ages 0-19.

“Usually ages 35-45 have the highest prevalence, but 2016 was particularly wide spread here,” said John Giampaolo of Cardinal Innovations, which provides mental health resources to the region.

But despite being swamped by loss, Fallen and other Stanly residents are looking for ways to confront suicide. Particularly this month.

Along with being hurricane season, September is National Suicide Prevention Month, Fallen explained, and like people recovering after a hurricane, those left behind by suicide are building something from the devastation.

Trending

“Because if we can do something to change things, their story doesn’t end,” Fallen said. “We can carry it on.”

A Personal Quest

For Fallen, that started out as a simple quest for answers.

Lauren was a fighter, he explained. She wasn’t one to just give up. So before she died she must have struggled with something for a long time.

“I wanted to understand,” Fallen said.

He plunged into researching and reading anything he could find about suicide. Pamphlets from therapists, webpages by national agencies, booklets on mental health. The more he read about the warning signs, the more he saw hints in the events leading up to Lauren’s death.

“That was really tough, realizing that,” Fallen said. “If I’d known beforehand, maybe I could have done something about it. But you can’t go back and change that.”

The shock eventually led Fallen to an awareness event sponsored by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Known as the Out of Darkness Walk, it opened up a chance for him to talk with people about his misunderstanding Lauren’s struggle.

“It was such a relief to finally talk about it,” Fallen said, recalling a conversation with one of the AFSP reps. “As soon as I told her I’d lost my friend she dropped what she was doing and hugged me… later that night, I put Lauren’s name on a memory wall, there… that was a big moment for me, being able to do that for her.”

In order to make a difference moving forward, he also decided to join the AFSP efforts. After all, if talking about the problem helped him, how much more could it help people like Lauren, he wondered.

In fact, according to the AFSP, most people who die by suicide struggle with brain conditions that limit their ability to interact with others and see positive outcomes to their situation.

“They literally have a hard time talking about it,” Fallen said. “They need people who aren’t afraid to do that for them. To ask them the tough questions.”

However, in a culture where suicide is such a taboo subject, that’s not natural for most people. Not even for people who’ve suffered a loss like Fallen.

So after going to the Out of Darkness walk, Fallen started taking a Talk Saves Lives class to train himself on how to do that.

“One of the biggest things they taught us is how suicide isn’t caused by asking about it,” Fallen said. “You’re not going to put that idea in someone’s head… Instead, it’s usually a relief when you ask them. They can finally say something.”

With an ever increasing number of mental health calls coming into the police department, that’s been a useful tool in his profession, too. Not only does Fallen ask those at such an incident about suicidal thoughts, but he also makes a point of finding out any emotional struggles they’re facing, like depression or anxiety.

“At first they’re like, you don’t really care, but then I show them (the AFSP bracelet) I always wear and tell them about Lauren,” Fallen said. “They can tell it does matter to me and they open up.”

In order to pass that onto others, Fallen got certified as a Talk Saves Lives instructor, as well. His first class was at Norwood United Methodist Church in June. He will host another at Pfeiffer University this week, and is available to host other classes, as well.

“Lauren’s part in the story may have ended the day she died, but I’m carrying it forward,” Fallen said. “It’s just part of my life now.”

A Coordinated Effort

Giampaolo and other healthcare professionals hope it will become a part of the county’s lifestyle as well.

Back in 2015, Stanly ranked 13th in the state for suicide rates, he noted.

“And people wanted to do something about it,” Giampaolo said

So local health agencies decided to build up a better grasp by forming the Stanly County Suicide Prevention Task Force.

Backed by Cardinal Innovations, Atrium Health, the county’s health department and emergency services, the task force started doing much the same thing Fallen did after Lauren’s death: research.

However, instead of focusing on the suicide itself, they focused on Stanly’s awareness of it: pulled targeted suicide data, researched available resources, canvased locals about educational efforts.

In the process, they found the county had a soft spot when it came to that kind of knowledge.

“There just weren’t many groups putting out information, not many classes,” Giampaolo explained.

“There just weren’t many groups putting out information, not many classes,” Giampaolo explained.

And while law enforcement officers had some training for mental health situations, it was scattered and varied.

“So the task force took on more of an educational focus,” Giampaolo said.

Along with facilitating communication between the different professional departments, the task force jointly funded efforts to create educational materials like “rack cards” — small informational fliers about suicide warning signs and resources.

It also started pushing Crisis Intervention Team training for law enforcement and other emergency responders, a section of which deals with mental disorders and suicide specifically.

“Basically, anyone can call in and ask for a CIT officer to help with mental health situations,” Giampaolo said.

CIT training has started including a Talk Saves Lives section in that training recently, Fallen added.

“It’s been good to see more people learning about that,” Fallen said.

Still, the biggest challenge for the task force is public engagement. Suicide is not an easy subject to talk about, so getting the people to come out and do just that isn’t easy.

Which is where individuals like Fallen are so important, Giampaolo said. Those with a personal connection to suicide have had a lot of success connecting with people in the Stanly community, he said.

For example, their biggest public engagement events have been in coordination with the privately launched group Hope Now, founded by a mother who lost her son to suicide. Their events drew about 50 people each, which fueled interest and support for the Suicide Prevention Task Force.

“We’re always looking for new ways like that to engage the public,” Giampaolo said.

And so between passionate individuals and focused professionals, perhaps Stanly County will build some kind of shelter in the storm.

“I think we can do more,” Fallen said. “As long as we’re willing to step up.”

To find out more about mental health and suicide training opportunities through Cardinal Innovations, contact Giampaolo at [email protected].

To find out more about Talk Saves Lives training sessions with Fallen, visit his Facebook page “Where Hope Grows, Miracles Will Blossom” or email him at [email protected].