Historical Society remembers Stanly native, civil rights champion

Published 3:35 pm Saturday, July 14, 2018

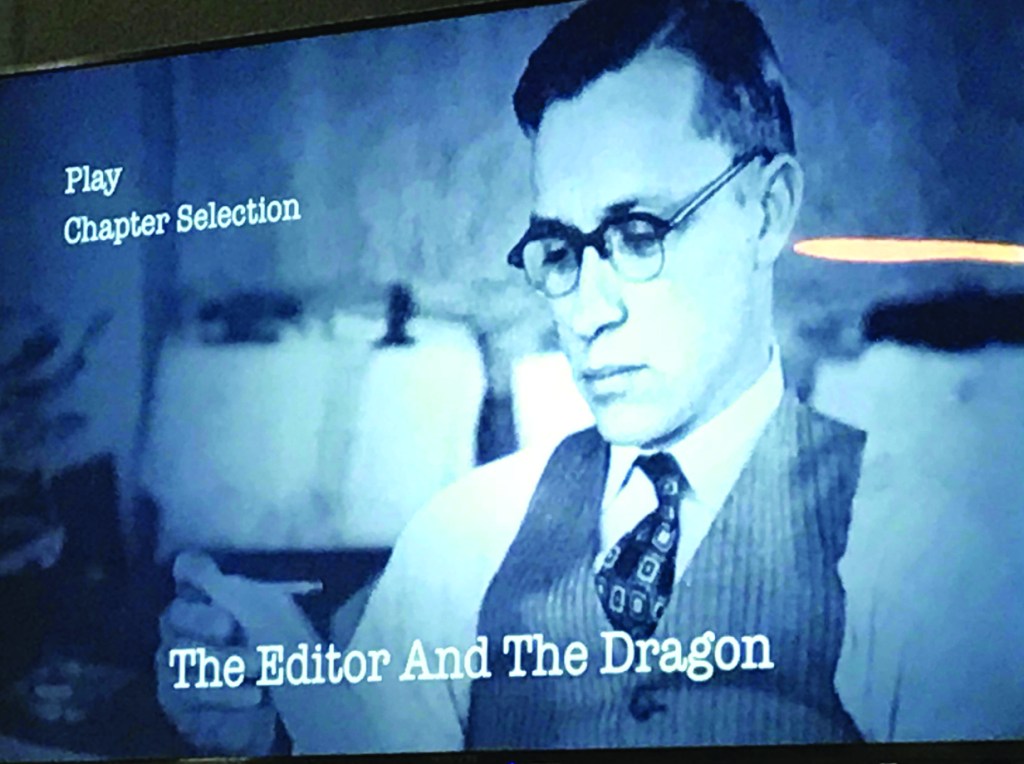

- The life of the late W. Horace Carter is told in “The Editor and The Dragon.”

At its annual banquet last month, the Stanly County Historical Society remembered the late W. Horace Carter, a native of the Endy community, whose stand against the oppression, hate and intimidation tactics of the Ku Klux Klan while editor of the Tabor City (NC) Tribune earned him and his publication the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service.

Carter, who died in 2009, was remembered by his son, Rusty, who spoke briefly of his father’s Stanly County roots and childhood.

Rusty Carter talked about his father, the late W. Horace Carter, for a program through the Stanly County Historical Society. There was also a viewing of the film “The Editor and The Dragon.”

Following his opening remarks, Carter presented the PBS documentary, “The Editor and the Dragon,” which chronicled the events of the early 1950s in Tabor City and Columbus County.

Horace Carter was a 1939 graduate of Endy High School, and was, according to his son, “the first Endy graduate to ever attend college.”

While in high school, Carter worked as a sports writer and typesetter for The Stanly News & Press before entering the University of North Carolina. At UNC, he served as editor of the student newspaper before graduating with a journalism degree.

Upon graduation from UNC, Carter served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After his military service, he came to Tabor City where he worked briefly for the town’s merchants association before establishing the Tribune as a weekly newspaper.

After witnessing a parade through downtown Tabor City by the Ku Klux Klan on July 22, 1950, Carter found himself repulsed by the actions of the Klansmen as well as by the fact that many made no effort to hide their identities and were actually prominent members of the community.

In response to what he witnessed, Carter penned an editorial, “No Excuse for KKK,” which ran in the July 26 Tribune. This opinion piece became the first of more than 100 such articles published over the next three years in which Carter expressed his opposition to the KKK’s schemes, beliefs and violence.

The general customs and traditions of the South in the 1950s, however, were not accommodating to Carter’s opinions on the Klan, and resulted in much turmoil to the editor and his family, which included wife Lucille as well as Rusty and his two sisters, Linda and Velda. The turmoil ranged from threats of an advertising boycott of the Tabor City Tribune to death threats, to actual intimidation and violence directed at the Carter home.

“I was very young, and don’t remember a lot of details,” recalled Rusty when asked about his memories of that time, “but I do remember some tension,” noting that when threats were levied against his father, the three youngsters were usually sent to the houses of friends to spend the night.

“I can also remember that cars would surround our home at night with the lights shining in,” he said, “and there were also some crosses burned in our yard.”

The elder Carter’s courage and determination to stay true to his values paid off over time, however. His continued reporting of incidents of violence, bullying and fear-mongering by the Klan, combined with his outspoken opposition to the organization’s racist and terrorist tactics, uncovered numerous violations of federal law and resulted in the eventual involvement of the FBI.

By late 1952, more than 80 KKK members, including Grand Dragon Thomas Hamilton, had been arrested on more than 200 charges.

During his battle with the Klan, Carter had found a supporter in Whiteville News Reporter editor Willard Cole, who shared Carter’s beliefs and disdain for the KKK.

When the 1953 Pulitzer Prize for Meritorious Public Service was announced, the two newspapers and editors were recognized for “their successful campaign against the Ku Klux Klan, waged on their own doorstep at the risk of economic loss and personal danger, culminating in the conviction of over one hundred Klansmen and an end to terrorism in their communities.”

Rusty Carter, in remembering his father at the conclusion of the program, described him as, “enormously proud to be from Stanly County.”

“He loved Stanly County and the Endy community,” said Rusty, “and he never broke from his roots.”

When asked how his father felt about the changes the country had gone through since the 1950s until his death, Carter stated that times and beliefs had changed more than his father did.

“Dad was a number one ‘God and Country’ guy,” said Rusty. “In the 1950s, he was considered an ‘enlightened liberal’ because he did not believe in what the Klan stood for. But in no way would he be considered a ‘liberal’ now. He was actually a conservative Republican at the time of his death. When the government stepped in during the ‘Great Society’ era and started trying to do it all, that’s when he had enough.”

The documentary “The Editor and The Dragon…Horace Carter Fights the Klan” can be viewed online at: https://video.unctv.org/video/unc-tv-presents-editor-and-dragon/ .

Toby Thorpe is a freelance contributor for The Stanly News & Press.