Former Richfield School students create memorial to honor teachers

Published 3:53 pm Wednesday, February 5, 2020

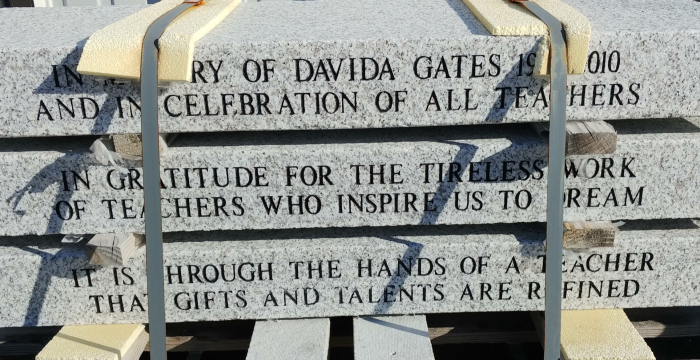

- Granite benches will also be erected alongside the memorial. (Picture provided by Willie Drye)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Most people remember the name of at least one teacher who made a valuable impact on their lives that extended well after the final school bell rang.

Richfield natives Willie Drye and Jim Misenheimer were lucky to have one of those teachers — Davida Gates, who was their sixth grade teacher at Richfield School for the 1961-62 school year.

Inspired by Gates, they decided to create a memorial at Richfield Park to honor both her and other teachers who have made an impact in lives in Stanly County and beyond.

Trending

“You frequently see memorials to military personnel and police officers and that’s fine and as it should be, but one of the things I think that motivated us was that we realized that we think teachers deserve a memorial as well because teachers help build what the cops and the soldiers protect,” Drye said.

The memorial will be an ellipse, 30 feet by 20 feet, with a wall raised slightly above the floor of the memorial, Drye said. The wall will hold a plaque explaining the purpose of the memorial.

The plaque will read: “In gratitude for the tireless work and patience of TEACHERS. They help us find our purpose in the world and inspire us to try to make it a better place. A teacher’s influence is eternal. It is through the efforts of teachers that the love of knowledge is kindled and gifts and talents are discovered and refined and used for the betterment of our society.

The memorial, which is being built at Richfield Park, will honor teachers. (Picture provided by Willie Drye)

About Davida Gates

Drye remembers Gates was an unusual teacher. While she was a strict disciplinarian who made sure her students followed the rules and exhibited good manners, she was “sort of like a beatnik,” and would wear jeans and sandals to class.

She let her students know there was a bigger world out there than just Richfield by taking them on field trips to Charlotte and other places.

But Drye said she made an extraordinary effort to connect with her students and helped them to discover and develop whatever talents lied within them.

“She saw something in me and encouraged me and gave me opportunities to try to develop as a storyteller and writer,” said Drye, who is an award-winning author and journalist and currently a contributing editor at National Geographic News.

“She taught with what little she had to work with,” Misenheimer said in terms of teaching materials, “but she opened up our world,” including telling students about the different states she had visited.

Though his class had a reputation for being difficult, Drye said Gates “pretty much tamed the class.” Gates taught at Richfield School from 1958 until 1962.

Davida Gates taught sixth graders at Richfield School from 1958 to 1962. (Picture provided by Willie Drye)

As the years passed, Drye, Misenheimer and his two brothers, Robert and Charles — who were also Gates’ students — remained close and never forgot Gates.

“It seemed like when we would be sitting up late at night just talking and having a beer, Ms. Gates’ name would always come up,” Drye said, “and we would recall some kind of influence that she had on us.”

In 2010, the men discovered Gates had retired from teaching and was in Livingston, Texas, living at the Escapees CARE Center. Charles had kept in correspondence with Gates over the years and happened to have her Texas address. They decided to go on a road trip to reunite with their sixth grade teacher.

They spent several days with Gates in March 2010 “and she was just delighted to see us,” Drye said. He even gave her his first book “Storm of the Century: The Labor Day Hurricane of 1935.” Though her vision was not good, she read it and wrote Drye a letter about how much she enjoyed the book.

Concerned with her dilapidated living conditions, the men talked about trying to find Gates a new place to live. Once back in Stanly, they corresponded with some of Gates’ other students about ways to help their former teacher. They raised money and connected with some of Gates’ friends in Texas who were able to obtain a FEMA trailer that had been used in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Once the trailer was brought to Gates, she suffered a stroke in May 2010 and died soon after.

Drye said Gates, who was an avid hiker, wanted her remains to be cremated and scattered in either the Rocky Mountains, the Everglades or the Appalachian Trail. Since Gates had no family, one of her friends sent her ashes to Drye at his home in Plymouth.

Several years later, Drye and Misenheimer took the ashes and drove to the Fontana Dam (which crosses the Appalachian Trail) in western North Carolina to fulfill her wishes. They spotted a sign outlining the rules of the trail, which immediately made them think of Gates.

Drye thought: “This is perfect, Ms. Gates is all about rules, we’ll do it right here,” and they scattered her ashes.

Sometime after the trip, Drye, Misenheimer and other classmates talked about creating a memorial for Gates which eventually expanded into a memorial for teachers.

They took a proposal to the Richfield Town Council around 2011 or 2012, which it approved, and they have been raising money for the memorial ever since.

Classmate Bill Barringer, who is a retired engineer, and Randy Sells, who is a stonemason, are donating their time to erect the memorial. Misenheimer said there’s a “good chance” the memorial will be finished by the end of the year.

Misenheimer said there will be space for at least two trees and at least 200 bricks inside the ellipse monument. There will also be granite benches.

Anyone wishing to contribute to the cost of the project can make checks payable to Teachers Memorial Fund at First Bank, P.O. Box 6, Richfield, NC 28137.

If people would like more information about the memorial, contact Willie Drye at [email protected].