Stanly elementary teachers connect with students through science of reading

Published 2:13 pm Friday, May 12, 2023

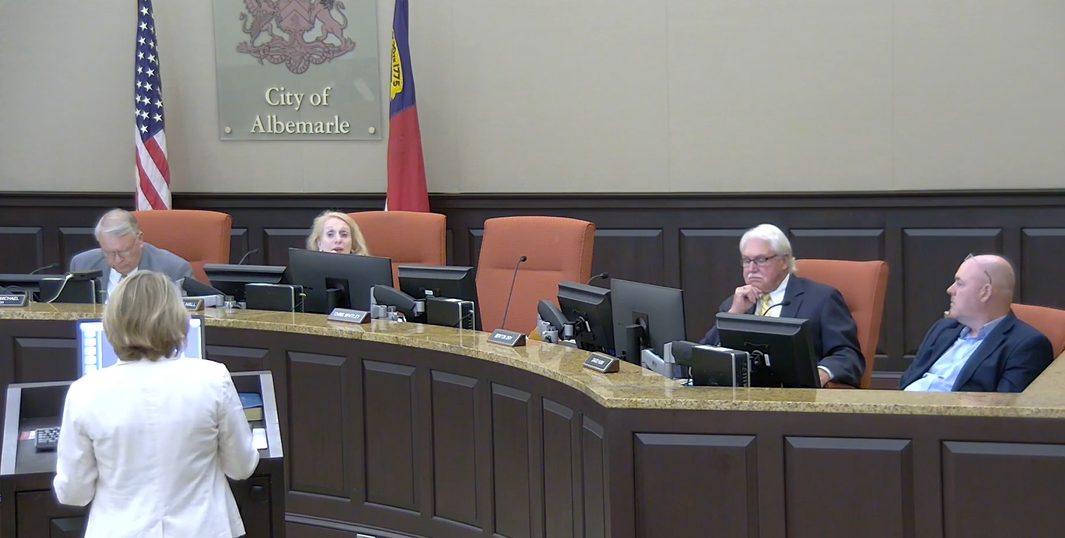

- Badin Elementary teacher Jennifer Baucom works with Jaxsan Sturdivant and Ella Averette.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

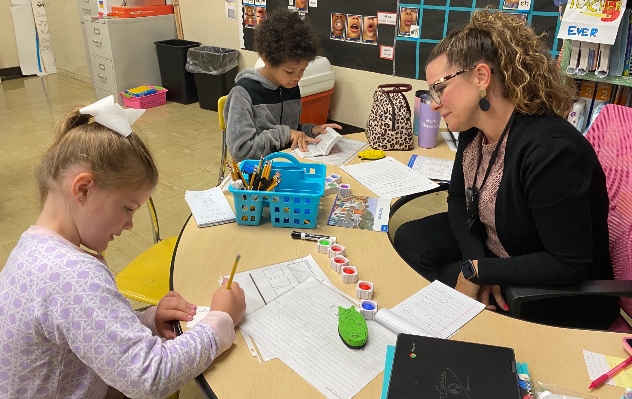

Students in Kim Napier’s second grade class at Norwood Elementary stood at the front of the classroom performing a hand-chopping motion as the teacher called out several words.

The word “calendar” received three chops (cal-en-dar), as did “multiply” (mul-ti-ply) and “investment” (in-vest-ment).

Next, as Napier listed other words, students listened for the middle sound to determine into what category, such as long vowel or vowel team the words fell.

Trending

These are just a few of the daily exercises Napier goes over with her students, combining physical movement with learning to decode how words are pronounced, to help her students learn to read.

“It’s just interaction,” Napier said. “It’s just movement and it’s helping them remember. It’s also repetition, lots and lots of repetition.”

Norwood Elementary’s Kim Napier goes through interactive exercises with her students.

These techniques seem light years ahead of how most adults learned to read, with programs like Hooked on Phonics and through techniques like guided reading and memorizing simple sight words.

That’s because the instruction is part of a new statewide training elementary and pre-K teachers across the district have taken part in called Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS), which highlights the science of reading.

The training provides teachers with the research, depth of knowledge and skills to make improvements in the literacy and language development of every student.

Norwood curriculum coach Bev Russell said she has seen students’ “fundamental skills” develop quicker than they have in the past.

Trending

“Kids are sponges,” said Napier, who’s been teaching for almost 30 years. “If you tell them and you teach them, they will rise to the occasion.”

Her second-grade students learn to distinguish between long vowel, when a sound matches the pronunciation of the word (like “baby”), vowel team, when two vowels make one sound (“play”) and diphthong, the combination of two vowels in a syllable (“coin”).

In a typical exercise, Napier goes through a call-and-response method to help kids apply what they’ve learned.

“Grain,” Napier told the class.

“Grain,” the students eagerly responded, slowly sounding out the word. “A-A-A-A-A-A…long vowel.”

“Blown,” Naiper said.

“Blown,” the class responded, again slowing sounding out the word. “O-O-O-O-O-O…vowel team.”

The students responded to several other words including “truth” and “hawk,” which they correctly identified as diphthongs.

Then came another challenge: Napier gave the students a portion of a word and a beginning sound, which they had to combine to form a whole word.

“‘Eople’ add ‘p,’ ” Napier said.

“‘Eople,’ ‘people,’ ” the students responded.

“‘Unday’ add ‘s,’ ” Napier said.

“‘Unday,’ ‘Sunday,’ ” the students replied.

How LETRs came to Stanly

The training was first introduced to Stanly County Schools several years ago by former superintendent Dr. Jeff James, well before much of the rest of the state knew about it, Chief Academic Officer Lynn Plummer recalled.

“He came to me one day, and on my desk was laying all this science of reading research from Mississippi and he said, ‘We can’t move forward with any other literacy programs or curriculum until we jump to this,’ ” Plummer said.

After decades of steadily falling scores in third-grade reading proficiency, the state enacted Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021, which modified the state’s Read to Achieve program with an emphasis on the science of reading. Schools began implementing the training this year.

According to the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, the science of reading “means evidence-based reading instruction practices that address the acquisition of language, phonological and phonemic awareness, phonics and spelling, fluency, vocabulary, oral language and comprehension that can be differentiated to meet the needs of individual students.”

SCS was one of 36 school districts enrolled in the second group of LETRS training in January 2022. Teachers who started with the school district this year are part of the third group.

“LETRS is nothing more than a professional development session … that is teaching the science of reading and digging back into the smallest microbes of what reading is,” Plummer, then director of elementary education, told the Stanly County Board of Education about the training in December 2021.

“We have smart teachers, they know their kids and they know what they need,” Plummer added. “Roll your own things into it, but this gives you a foundation to start with. Start with this and then go beyond.”

Teachers like Napier have been able to go above and beyond, finding creative ways to engage with their students.

Since learning about the program and taking the necessary training (most teachers have completed six of eight sessions), Napier has grown more confident in her ability to connect with her students.

“It’s definitely made me more purposeful in each and everything that I do,” she said.

‘Big year of growth’

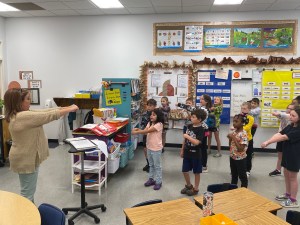

The training has been beneficial for Napier’s colleague, third-grade teacher Allison Vanness. She works with her students on prefixes and suffixes, vocabulary and understanding the origins of words.

To get students engaged and moving, Napier creates physical movements to associate with each word her students learn. For the word “hail,” students make hand motions to signal rain falling from the sky, while for “distract,” students turn their heads the other way.

Norwood Elementary third grader Hinley Hatley plays the dice game “Trash or Treasure” with teacher Allison Vanness.

Her students also play a game where they roll three lettered dice and form words, both real (known as “treasures”) or nonsense words (“trash”).

“That’s part of their assessment,” Napier said of the game. “They have to know nonsense words because when they know nonsense words, you know they can accurately decode and they’re not just memorizing (real) words.”

For 9-year-old Hinley Hatley, who played several rounds of “Trash or Treasure” with Napier, the best part of LETRS training is “that I learn new stuff each time I read.”

Vanness, who teaches reading to all third-grade students, said she has seen “tons of growth in these children, in their reading abilities and their fluency and on all of their assessments and check-ins.

“We’ve had a really big year of growth.”

‘Not afraid of language’

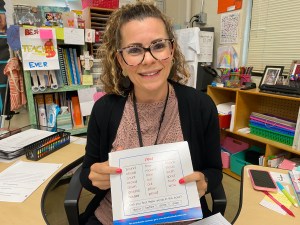

About 20 minutes away, at Badin Elementary, second grade teacher Jennifer Baucom was busy working with her students in small groups, making sure they can correctly spell certain words, such as c-o-u-n-t.

Pinned to her wall is The Vowel Valley, a chart detailing the visual representation of the mouth movements for each vowel. Pronouncing the “o” in “so” or “hope,” for example, requires a slightly different mouth configuration than pronouncing the “o” in “fox.”

“It’s basically redefining how we approach reading,” Baucom said about the LETRS training, as she was working with 8-year-olds Jaxsan Sturdivant and Ella Averette.

“We’re really trying to help students understand that reading comprehension really comes from language comprehension mixed with decoding.”

Badin Elementary’s Jennifer Baucom has taught at the school for 18 years.

The decoding comes as students learn the foundations of words. For example, just because two words have similar sounds does not mean the vowels are the same.

The students learn, for example, that both “count” and “now” have similar “ou” sounds, but are spelled in different ways.

The students learn to distinguish between similar sounding words as they read what Baucom refers to as “decodable texts.”

To help her students count syllables, Baucom taught them an easy trick: when saying a word, place your hand level below your chin. How many times your chin touches your hand determines how many syllables are in the word.

“At first we felt really silly doing it,” she said, adding her students did it so much, that eventually they no longer needed their hand. They just felt for when their chin dropped.

“That helps them with word attacking when they are spelling.”

Badin Elementary second grader Ella Averette displays a technique to help count syllables.

As students learn to decode words and understand proper vowel sounds, Baucom said, their confidence increases.

Both Sturdivant and Averette mentioned how Baucom’s teaching has helped them take on trickier words such as “question,” which had been a challenge for Averette. When spelling it, she kept placing the “o” in front of the “i.” One of Sturdivant’s tough words was “siren.”

“We’re not afraid of language. We’re not afraid of vocabulary,” Baucom said. “We’re not afraid of tackling what we call big words or large words… The confidence that I’ve seen in students has been a really big shift since doing the science of reading.”