Korean War nuclear veteran, Oakboro parade grand marshal recalls experiences on Marshall Islands

Published 8:58 am Friday, November 11, 2022

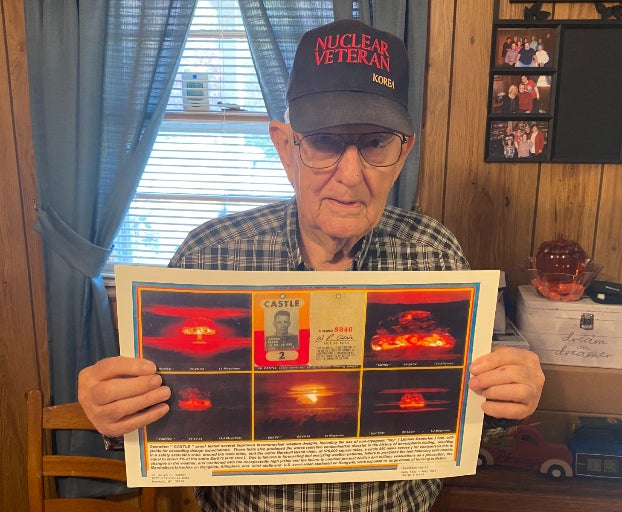

- Ralph Hudson, who was part of a secret group that played a role during Operation Castle in 1953, talked about his experiences from his home in Cottonville. (Photo by CHRIS MILLER/staff)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It was early in the morning on March 1, 1954, before the sun came up, when Norwood native Ralph Hudson witnessed history. He was one of the few who saw firsthand the detonation of Castle Bravo, the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands.

Standing on the beach about 175 miles from the blast, “the whole world went bright, 10 times brighter than the noon day sun,” he recalled. “I lost my sight, I lost my hearing, I got knocked out.”

The blast was so bright that it did not get dark again until the next night, he said. Bravo was 1,000 times as powerful as the U.S. nuclear weapons used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Trending

Overall, between 1946 and 1958, the United States conducted 67 nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean.

Hudson, who was part of the U.S. Army, and the other eight members of his top secret group spent about a year in the Marshall Islands, where they witnessed an additional five nuclear blasts as part of the nuclear testing program Operation Castle. Sworn to secrecy, Hudson could not divulge any information regarding his mission until the early 2000s, when he was cleared to finally talk about it.

Hudson, 90, has since relayed his story to classrooms, churches and other organizations around the county.

“It’s something very few people know anything about so when I start talking about it, they look at me and say, ‘Are you crazy?’ ” he said.

In recognition of Hudson’s service to his country, he was selected as this year’s grand marshal for the Veterans Day Parade at 11 a.m. Saturday in Oakboro.

Told about his selection about two months ago, Hudson, a member of American Legion Post 76, was equal parts honored and elated.

Trending

“It was so great. I have never had that type of reception,” he said, adding he almost jumped to the ceiling when he found out.

Ralph Hudson and his wife Ann look through old papers he’s collected about Operation Castle. (Photo by CHRIS MILLER/staff)

Hudson grew up in Cottonville and worked for Collins & Aikman for a few years before getting drafted into the U.S. Army in 1953 for the Korean War. He attended basic training at Fort Eustice in Virginia and amphibious training at Fort Story in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

When Hudson and his team first learned about the mission in the Marshall Islands that would take them across the world, they were excited. However, Hudson said they were not told about the physical dangers of the nuclear radiation.

After being told about the need for soldiers to operate Army duck boats, which can travel on land and water, and travel to Bikini Atoll, Hudson recalled one of the men in his unit said the location was where “they modeled Bikini bathing suits at,” which was met with great laughter.

“That’s why they all volunteered,” Hudson’s wife Ann said with a laugh.

Aside from Hudson, there were two other men from North Carolina: Billy Sides from Albemarle and another man from King.

Ralph Hudson was in his early 20s when he traveled to the Marshall Islands in 1953. Photo courtesy of Ralph Hudson.

The nuclear testing program was so secret that while home for a two-week furlough before heading to the Marshall Islands, the CIA sent people to follow Hudson, who did not know about the mission at the time.

“They followed me day and night,” he said.

Hudson arrived on the islands in 1953, several months before the nuclear testing began.

As part of Joint Task Force 7 (JTF-7), Hudson and his crew aided in the transportation of nuclear bombs for testing in the Marshall Islands as part of Operation Castle. He said he was personally in charge of nine duck boats and his unit regularly secured the many islands before the testing occurred.

After the bombs detonated, he would drive the boats onto the islands and check for radiation. Whenever anyone came onto the islands following a blast, he checked them for radiation and sent them for a bath.

“We were the workforce,” he said.

With the islands being so close to the equator, the temperatures were often stifling hot, sometimes reaching as high as 135 degrees Fahrenheit.

When the first bomb, Bravo, detonated, the yield was 15 megatons of TNT, about 2.5 times the predicted 6 megatonnes of TNT. The radiative material — he called it “Bikini ash” — caused by the bomb fell on Hudson and his men and created skin issues. With the test more than twice as powerful as predicted, he said it burned the paint off ships 150 miles away and busted the fuel tanks of nearby planes.

When interviewed a few years ago by Matthew Peek, a military collection archivist, Hudson recounted a particularly harrowing occasion where his duck boat got stuck in the mud as he was leaving. Had it not been for a helicopter which happened to be in the area that picked him up, Hudson would have been incinerated.

As the bomb Nectar was detonated, while laying face down on the beach, about 40 miles away, with a raincoat over his body, he could visibly see the bones in his arms.

Hudson was discharged in January 1955. He contacted Collins & Aikman upon coming home and quickly resumed his work for the company. He worked there for the next 45 years.

The continued exposure to the nuclear radiation impacted the health of each man in Hudson’s unit, as many developed cancer and other health struggles. Hudson has had four heart attacks, four strokes and a host of other complications. He is the last surviving member of his unit.

“In other words, he is a miracle,” Ann said.

Hudson is a member of the National Association of Atomic Veterans, a group whose purpose is allowing “the U. S. Atomic Veteran Community to speak, with a single voice, to their inability to get a fair hearing related to their developing (radiogenic) health issues that may have been precipitated by their exposure to ‘ionizing’ radiation while participating in a nuclear weapon test detonation, or a ‘post-test’ event.”