STANLY THE MAGAZINE: Ruth and Talmadge Moose – a love story of two creators

Published 3:23 pm Thursday, October 20, 2022

- “Clay Banks” by Talmadge Moose. (Contributed)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

They met at a picnic in 1952. He had graduated from Albemarle High School the previous year.

She still had four years to go. He waited for her.

Talmadge and Ruth Moose were born and raised in Stanly County. She grew up in west Albemarle, the oldest child of Ardie and Vera Morris. He was the son of Cecil and Flora Moose and lived south of town toward Norwood where his uncles owned dairy farms — Mooseville, he called it.

Ruth says her mother took her to Montaldo’s in Charlotte to buy her wedding dress — a $25 bargain rack steal. She and Talmadge were married at Second Street Presbyterian Church in 1956 after she graduated from AHS.

“Talmadge had more ambition than anyone I knew,” said Ruth. “He was the first in his family to go to college. Pharmacy school at UNC-Chapel Hill was the plan.”

Instead, a last-minute change of heart — more like an admission of his heart’s true desire — drew him to Richmond Professional Institute at the College of William and Mary where he earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts.

Even if fine arts jobs after college proved elusive, Talmadge gained practical experience working in commercial art as a technical illustrator and an art director and spent his evenings and weekends doing freelance design work.

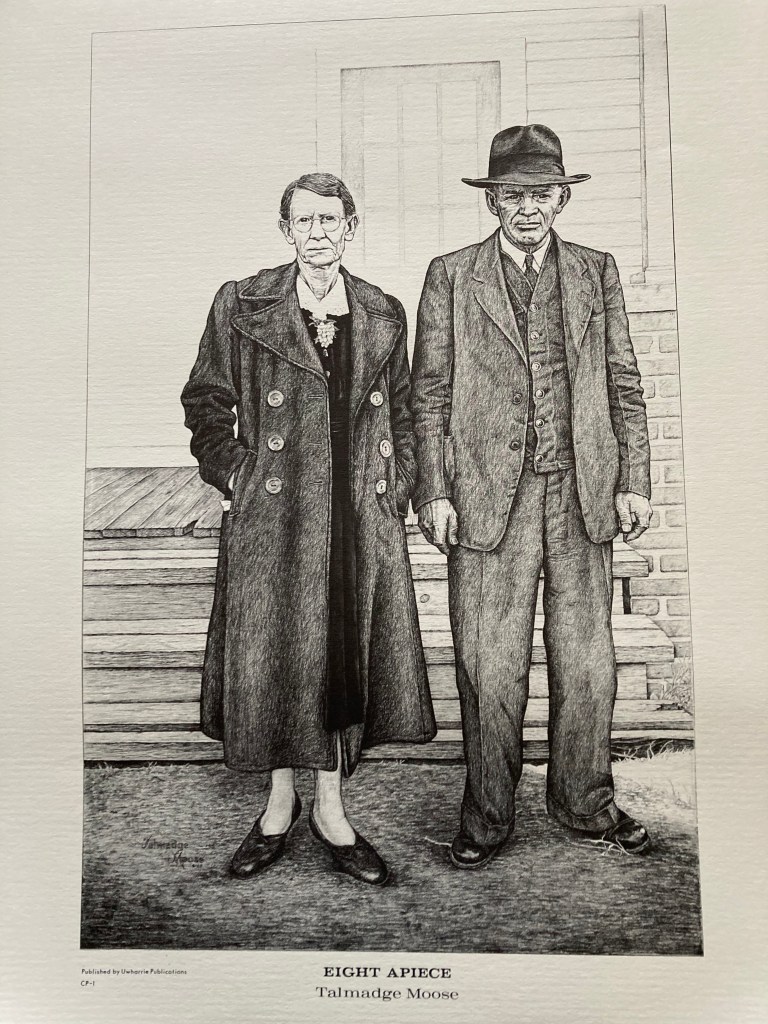

Talmadge and Ruth Moose met at a picnic in 1952 and were married a few years later. (Contributed)

The couple lived for a while in Winston-Salem, then Charlotte, then by 1972 they were back home in Stanly County building a home on Stony Mountain designed by Talmadge.

Stanly Technical Institute (now Stanly Community College) hired him to develop and teach the first commercial art courses there. He told one interviewer some of his students had never seen an original painting so his teaching plan was to “throw in fine art on the side because art is art is art. A student must learn painting before he can learn commercial design.”

Ruth says it only took one art book in the Stanly County Library to feed a boyhood appetite for the visual arts. Her husband’s first art hero was Norman Rockwell, the 20th century American painter and illustrator known for his “Saturday Evening Post” cover designs.

Talmadge also developed a fascination with the work of Andrew Wyeth whose favorite subjects were the land and the people around him.

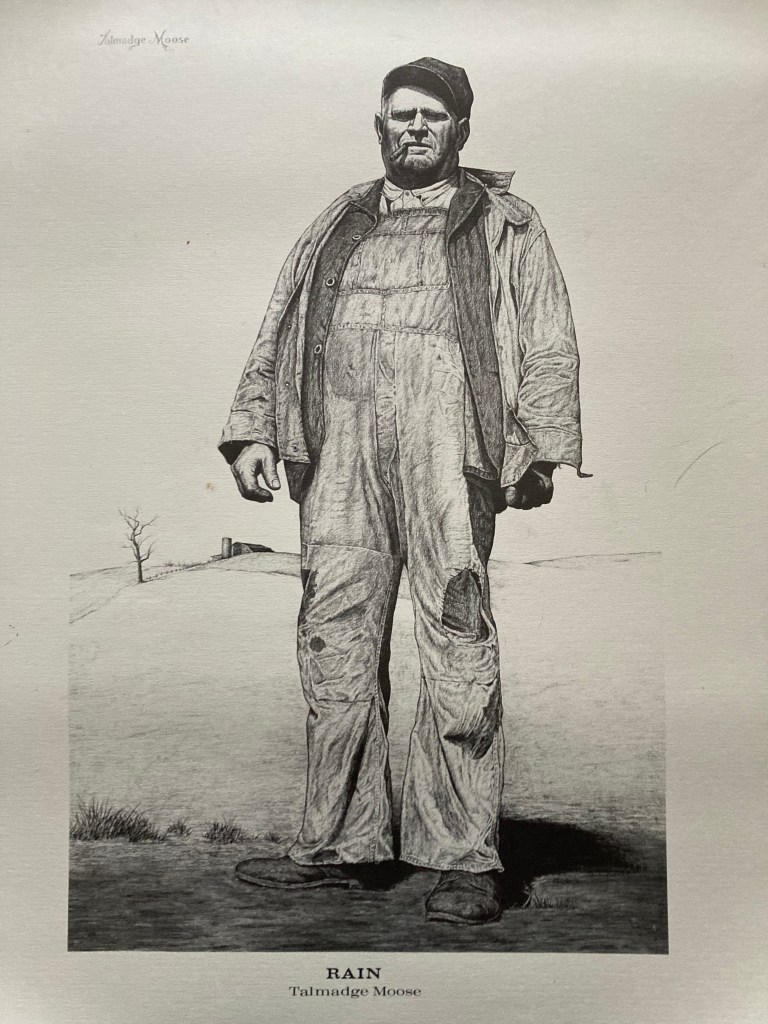

Though Talmadge worked in acrylics, oil, and watercolor, Ruth says his favorite medium was carbon pencil. With Eckerd’s No. 2 pencils he made meticulous pencil strokes, capturing, as he said, “the universal in the particular. Each subject relates to some part of my life, but by the same token it will relate to some part of each viewer’s life. There’s a Stanly County in everyone’s past.”

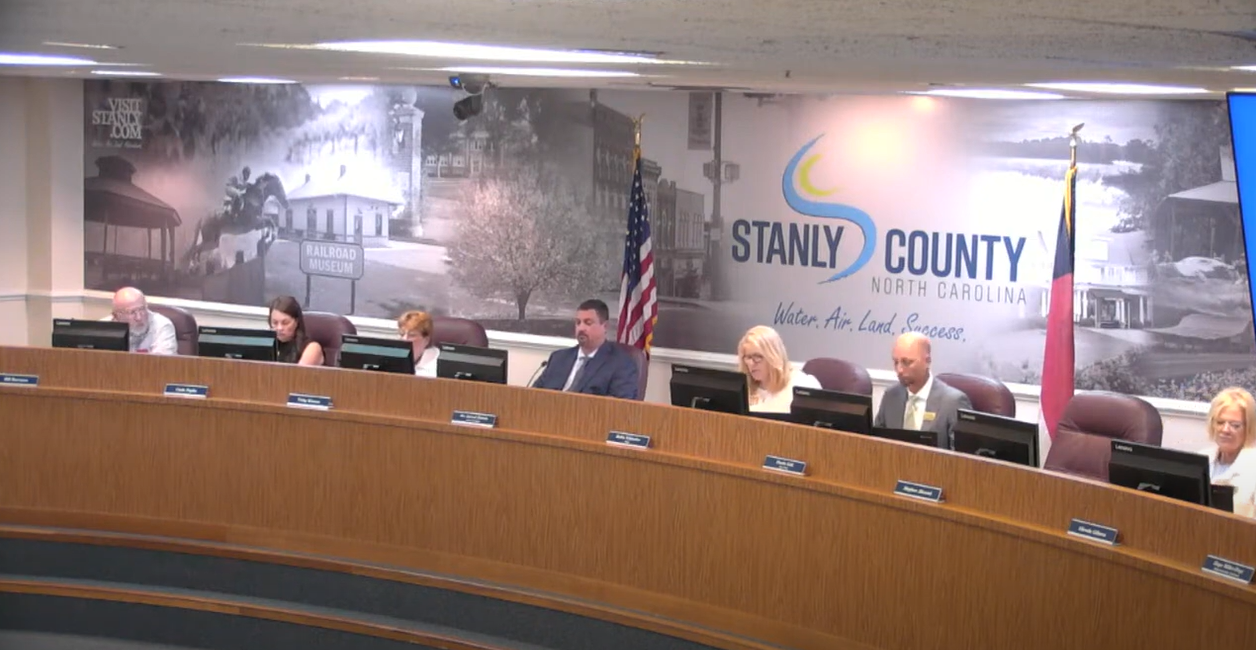

“Eight Apiece” was a portrait of Talmadge Moose’s grandparents. (Contributed)

One of Talmadge’s large award-winning pencil portraits first appeared as part of a 1970s exhibition at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. The details of coat buttons, worn spots and wrinkled faces are plainer than the photographs he often worked from. It was a portrait of his grandparents, named “Eight Apiece” and dubbed “Southern Gothic” by an Atlanta art critic who compared it to Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic” painting.

If Talmadge’s college studies and dreams seemed like “air castles” to his parents, Ruth’s high school courses kept her grounded.

At Albemarle High School she was placed in the vocational track that entailed classes until noon then a short walk to City Hall where she worked five afternoons a week and half a day on Saturday.

Diversified Education students were not expected to go on to college, but after marrying, she earned a bachelor’s in English and creative writing from Pfeiffer College (now Pfeiffer University), then in 1989 a Master of Library Science from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

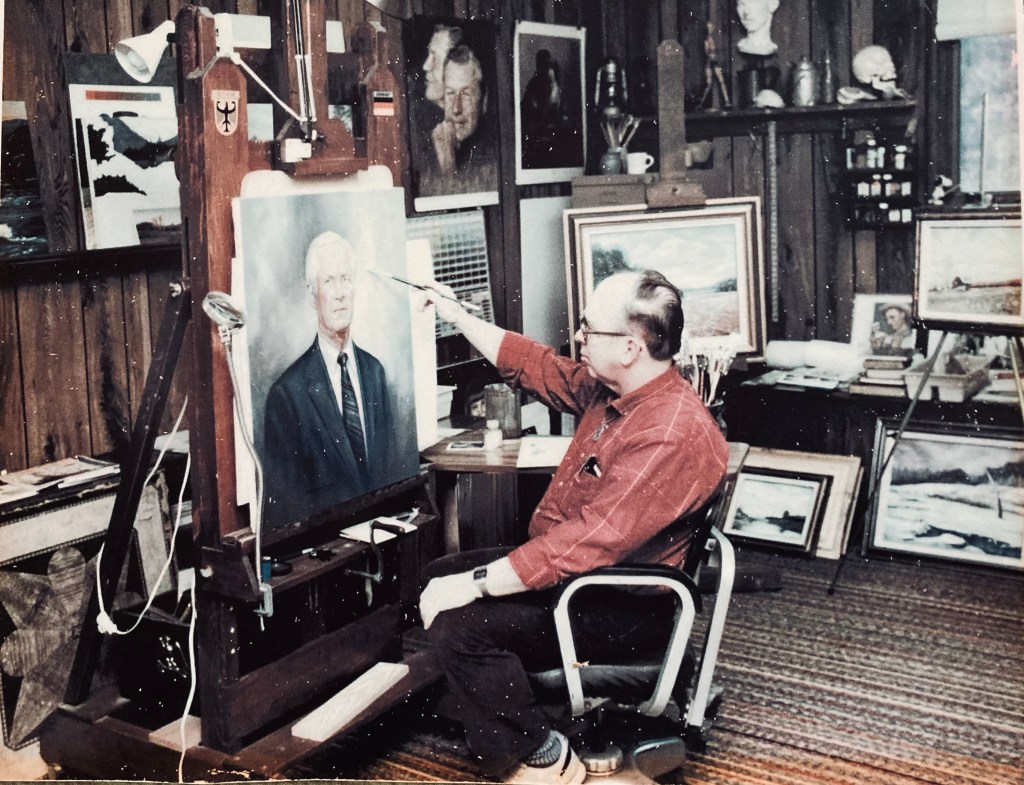

Talmadge Moose works in his studio. (Contributed)

Ruth values the skills she gained through the Diversified Education program.

“Shorthand teaches you to listen,” she says, and her typing know-how served her well for 12 years as she carted her Smith-Corona typewriter all over the Carolinas one week each month teaching poetry and creative writing in schools at all grade levels. She says she eventually wore it out typing three columns a week for the Charlotte News.

Years ago in Charlotte, Ruth began writing stories in short bits of time in between tending two young sons, serving as “office help” for Talmadge, attending PTA events and taking writing classes. She turned listening into a writer’s tool by making use of everyday conversational tidbits for her short stories and poetry. She found story ideas in newspaper fillers, headlines and the classifieds, and collected character names from obituaries.

Ruth also met other writers through the Charlotte Writers Club, like Dannye Romine Powell before she became a Charlotte Observer feature writer. And before Ruth’s short stories found their way into glossy magazines. The women gathered in Dannye’s kitchen to share their works in progress and to learn to see their own words through someone else’s eyes.

“When we built our Uwharrie home, we included side-by-side studios on the lower level of the house with equal square footage and floor-to-ceiling windows looking out on the woods and a small creek,” said Ruth. “When we worked, we mostly left each other alone. Our one rule was we couldn’t comment on the other’s work in progress.”

But they did work together on behalf of the arts in Stanly County through the Stanly County Arts Council. They served as co-chairs of the Artist Writer’s Dialogue.

“Rain,” a pencil drawing by Talmadge Moose. (Contributed)

Talmadge gave art showings in the Stanly County Public Library, at Pfeiffer and Stanly Community College. Ruth conducted poetry workshops in six elementary schools, formed writer’s groups and book clubs. She served as editor of the Uwharrie Review for several years. She undertook the collection of writings on poverty by N.C. authors which were published in a small book called “I Have Walked.”

Talmadge provided the cover illustration. Ruth’s poems were published in various literary reviews and her stories in magazines, such as Good Housekeeping, Redbook, Ladies Home Journal, The State (now Our State), and Atlantic Monthly. Her short fiction pieces were mostly about southern women, and full of realism and something one book critic called “Southern dailiness…loveliness and dignity amidst the meaner details of life.”

By 1987 Ruth was working as the reference librarian at Pfeiffer while driving to Greensboro on Monday evenings for her master’s studies at UNCG. She also taught a children’s literature class and worked one morning a week on her first novel.

In 1988 Ruth and Talmadge made a pilgrimage to England as part of a writer’s fellowship grant from the N.C. Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. They visited Dickens’ house, the homes of Beatrix Potter, John Keats and Jane Austen’s House Museum.

“When the docent turned aside, I put my hand on Jane Austen’s desk,” said Ruth.

Ruth’s tenure at Pfeiffer lasted until 1996 when her work caught the attention of the Creative Writing Department at UNC-Chapel Hill. They were looking for a writer of short fiction — Ruth’s first love and a natural fit. She also taught children’s literature classes and various workshops during her 15 years on the faculty.

She says she still gets wedding invitations from former students, and loves hearing from them.

“One former student has had a Netflix series made from two of her novels started in my class,” said Ruth.

Bridget Huckabee is a writing friend who’s known Ruth for many years and has high praise for her ability to critique without being critical.

“She’s a natural teacher, an excellent listener and gives generous help with all aspects of writing. She was the leader of our writer’s group, though she won’t admit it. We fell apart when she moved to Chapel Hill.”

Talmadge and Ruth were married 47 years and spent seven years together in Pittsboro before he died in 2003. They raised their sons, Lyle and Barry, and shared a passion for books, art, learning and making a difference. They earned awards too numerous to list and produced a significant body of work to share.

Ruth grieved deeply, but she worked through her grief by doing what comes naturally.

She wrote.

And wrote.

“I was in a writer’s workshop in Raleigh and had to come up with something,” she said.

She pulled the short stories together around a theme, and with the help of her editor at St. Andrews University Press, another book rolled off the press.

“The Goings on at Glen Arbor Acres” was released in May 2022.

Ruth moved back to Albemarle two years ago to be near her family. She donated 996 of Talmadge’s art books to North Carolina art institutions and still bookshelves overflow.

Talmadge’s paintings and drawings remind her of his work and of his words: “There’s beauty in red clay banks and the people who live among them.”