Historian, farmer discusses importance of longleaf pines in North Carolina’s history

Published 2:24 pm Tuesday, March 1, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“Here’s to the land of the long leaf pine,

The summer land where the sun doth shine,

Where the weak grow strong and the strong grow great,

Here’s to ‘Down Home,’ the Old North State!”

That is the first verse of North Carolina’s official toast, adopted by the General Assembly in 1957. Though many residents proudly know these words by heart, few people likely know the significance the longleaf pine has played in the state’s history, aside from a prestigious award given out to notable North Carolinians bearing the tree’s name.

Did you know, for example, that longleaf pine forests were a source of naval stores — especially tar, turpentine and pitch — needed by English merchants and the navy for their ships? Or that in order to properly harvest the trees, enslaved people from Africa were brought to the colony?

Trending

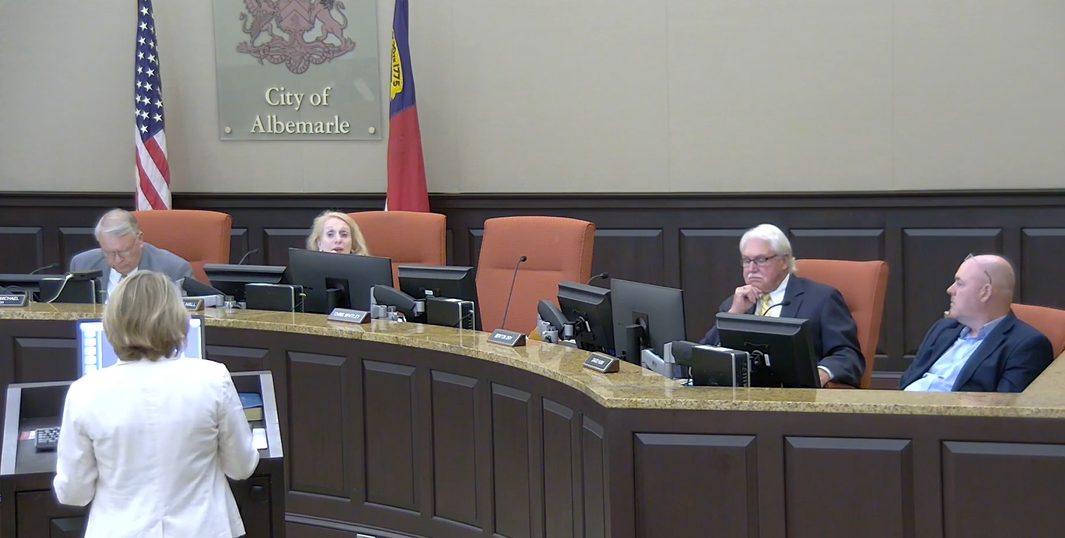

That was the subject for the Stanly County Historical Society’s first event of the year, a presentation called “Naval Stores and the Real Tar Heels: A Story About the Long Leaf Pines,” held Sunday afternoon at the E.E. Waddell Community Center. Earl Ijames, curator at the N.C. Museum of History and a seventh generation African American farmer, spoke to a crowd of close to 70 about the role the longleaf pine played in the state’s founding.

Earl Ijames hugs a 450-year-old longleaf pine. Photo courtesy of Pat Bramlett.

When Carolina was first chartered by England in 1663, it extended westward all the way to present-day southern California and about 93 million acres of long leaf pine forest grew from coastal North Carolina to east Texas. This made it the second most biodiverse ecosystem in the world.

One of the key reasons the British colonized the Carolinas, Ijames said, was because of these trees, which were coveted by the English navy to help construct their ships. The sap from longleaf pines was harvested and specifically turned into turpentine, pitch and tar. Tar and pitch were largely used to paint the bottoms of wooden ships, while turpentine was coveted for medicinal purposes.

To encourage the American naval stores industry, the English Parliament passed a law in 1705 that required the British Navy to pay inflated prices for naval store products including tar, pitch and turpentine. Lucrative bounties were offered encouraging English colonists, including those from islands like Barbados and Jamaica, to come to Carolina. These colonists also purchased enslaved people from Africa who would be the ones actually performing the manual labor.

Similar to the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s, the bounties offered to attract colonists to Carolina created what Ijames called the “first rush to an area to create almost an instant wealth.”

From about 1720 to 1870, North Carolina led the world in production of naval stores — an estimated 100,000 barrels of tar and pitch were shipped from North Carolina to England every year — but it came at a price: Once longleaf pines were harvested, the forests were often cleared for tobacco plantations. The naval industry became so popular along the coast that it led to the creation of two new seaports — Brunswick Town in 1725 and Wilmington in 1739.

Trending

Most of the enslaved people who hacked the trees to extract the tar pitch hailed from the Guinea region of Africa. The derisive nickname “Tar Heel” referred to these enslaved people who toiled away in the forests. About 54 enslaved men would tend to a typical 640-acre land grant of longleaf pines, Ijames said.

After the Civil War, during which many turpentine orchards were burned, the importance of naval store production declined as the tobacco economy emerged and iron-hulled ships were being built.

As of today, less than one percent of the original 93 million longleaf pines are still in existence. The largest single tract is around 600 acres located in Weymouth Woods near Southern Pines.

“Right here in our own backyard, we have an almost ecological crisis that could be tempered through a simple measure of replanting the tree that the good Lord put here originally,” he said.

To help save one of North Carolina’s treasured symbols, Ijames grows longleaf pines on his farm and works with groups across the state to plant more of the trees.

As a way of helping to ensure “the land of the long leaf pine” continues to have meaning in the state, Ijames brought a palm tree and a longleaf pine from his farm to be planted at the Waddell Center.

Pat Bramlett and Jim Sawyer plant a palm tree and longleaf pine at the E.E. Waddell Center. Photo courtesy of Pat Bramlett.