What happens to Albemarle’s abandoned buildings?

Published 3:00 pm Thursday, April 11, 2019

- The old Lilly's Auto Transport building on East Main Street across from Jay's Downtowner Restaurant has seen better days.

Any person with a keen eye driving around Albemarle will most likely spot a common problem of former small textile towns: abandoned and dilapidated buildings.

Some look bad and structurally unstable on the outside, while others that might seem normal on the outside look like an earthquake or tornado happened on the inside.

“We do have a major issue with abandoned and dilapidated buildings in the city,” wrote Kevin Robinson, director of the city’s planning and development services, in an email.

Trending

A big reason Robinson moved to Albemarle three years ago was due to the city’s “building environment” and “the wealth of old structures that give character to our downtown and our neighborhoods.”

While there is potential for these older buildings to be part of Albemarle’s revitalization, “unfortunately many have been uncared for, neglected, allowed to rot and now will not survive much longer,” Robinson wrote.

There are many reasons these properties have declined, Robinson wrote, including a slowly growing population with a declining demand for certain commercial and residential structures in recent decades, young family members moving away and abandoning family properties, landowners finding it difficult to balance lower rents and property upkeep, a slow economy, inadequate enforcement of the city code and a lack of resources over the years.

- Property next to Four Seasons Realty on East Main Street across from the Stanly County Public Library.

- Inside of the property next to Four Seasons Realty on East Main Street.

- Property across from The Stanly News & Press building on West North Street.

- The old Sammy’s Dry Cleaners building across from Five Points Public House on Pee Dee Avenue.

- The old Lilly’s Auto Transport on East Main Street across from Jay’s Downtowner Restaurant.

- A look inside of the property that used to be Lilly’s Auto Transport on East Main Street.

- The old Hal’s Restaurant building on North First Street.

The city, in accordance with state statues, addresses residential properties differently than commercial properties. State minimum housing code deals with the minimum standards that all habitable residential properties must meet, Robinson wrote.

Robinson added that while a house with a broken window is definitely a problem that should be addressed, the city prioritizes its efforts on residential properties that are structurally unsafe.

The majority of cases require several months, if not a year, to finish. A physical inspection and documentation of violations by a minimum housing code enforcement officer occurs first. The city then identifies and reaches out to the owner of the property to give it a chance to fix any of the violations.

Trending

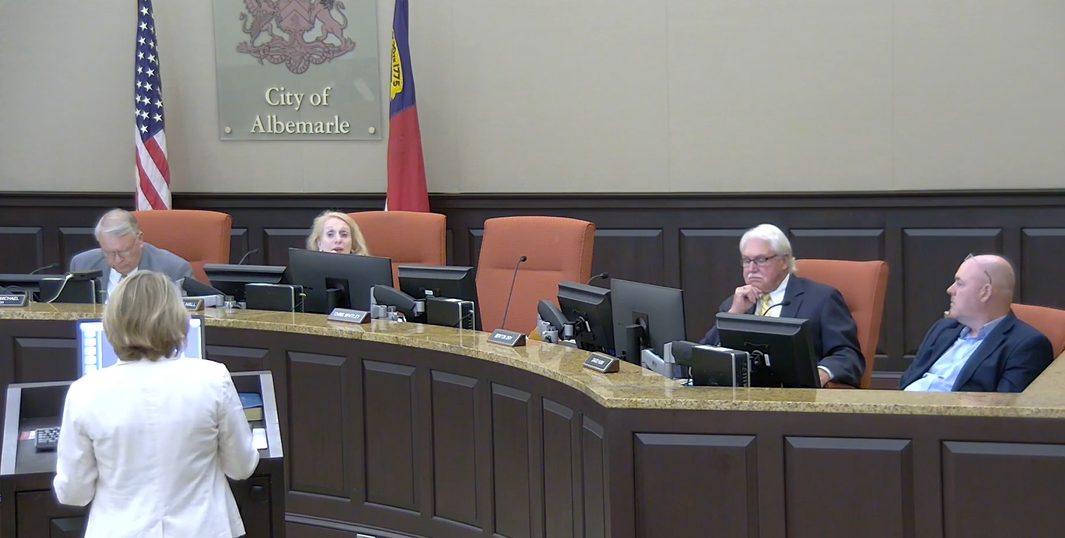

A public hearing is conducted before the City Council to discuss the housing violations and what the owner will do to try and meet the minimum housing standards. The city gives the owners time to try and fix the problems. Ideally, the property owners spend enough time repairing the property that it eventually meets the housing standards and the problem goes away, according to Robinson.

But if the city can’t reach the property owners or if the property is dilapidated beyond repair, the city’s planning department usually requests the City Council have a public hearing and adopt an ordinance directing city staff to try and fix the violations, which in almost all cases means demolition, Robinson wrote. Eleven properties were on the city’s demolition list last year.

A state-required asbestos assessment is performed on the property, often followed by asbestos abatement treatment of the house. Finally, there is a bid process to contract for the demolition of the property or the fire department conducts a training burn.

Robinson noted that the training burn has been a recent option because it saves the city around $6,000 to $7,000 and provides training for local fire departments.

But the process of taking a property through the minimum housing process all the way to removal can cost a minimum of around $3,000, all the way to around $15,000 if major asbestos removal or extensive clean-up and disposal is required, Robinson wrote.

It is the preference of the city for the property owners to either fix or demolish the home or sell the home to someone who has the means to do so, he said.

“The city is always exploring other options including partnering with preservation groups to help them acquire and fix these structures and initiating tax foreclosures on others when appropriate,” Robinson wrote.

Commercial properties require a separate commercial maintenance ordinance. The city is currently in the process of finalizing an ordinance for the council to adopt sometime in the coming months. Once that ordinance is in place, the process for working to fix deteriorated and dilapidated commercial structures will be similar to the city’s minimum housing standards, Robinson wrote.

Because many dilapidated commercial properties, like the ones downtown, are physically attached to other properties, it is likely that fixing or demolishing the commercial structures will be more expensive than the residential structures, Robinson wrote.

But with new economic development happening in the city, including the Pfeiffer University health campus being built and the Albemarle Hotel being turned into apartments, City Manager Michael Ferris hopes more people will decide to live and work in Albemarle, meaning some of the abandoned properties could take on a second life.

“If we change the economics of everything,” Ferris said, “we (the city) don’t have to get involved and it’s worth somebody’s investment that they can do it (fix the property) themselves.”