Larry Penkava Column: Credit where credit is due

Published 6:34 pm Friday, September 28, 2018

Thank goodness for Mr. Walton.

Douglas Walton, to be exact. He was the commercial arts teacher at Franklinville High School back in the 1960s when I took his typing class.

Larry Penkava

Our class — 1965 — was told we needed to be able to type if we planned to go to college. So those of us in college prep took Mr. Walton’s typing class during our sophomore or junior year.

He was the epitome of the stereotypical office manager: strict but not overbearing, a stickler for detail and a straight man to all the class clowns.

Mr. Walton, with his curly blond hair and horn-rimmed black glasses, was always smartly dressed in blazer, slacks and perfectly-knotted tie.

He also exhibited the patience of Job, not inclined to berate a student who had yet to master the intricacies of QWERTYUIOP. Instead, he encouraged said student to continue practicing the keyboard drills that he had instilled.

Those drills included learning the correct finger positions on the home keys: right-hand fingers rest on J, K, L and ;. Left-hand fingers rest on F, D, S and A.

From there we practiced which finger went to what keys beyond the resting key. Right pointer finger, for example, hit J, H, U, Y, N and M, moving from the middle row to the upper row and back down to the lower row.

Mr. Walton taught us the responsibility of each finger, which he drilled us on for the first few weeks of the class. When he felt we were sufficiently adept, he gave us typing assignments to perform.

Those assignments grew increasingly complex as the school year progressed. The most difficult exercise, for me, had to do with setting tabs and columns.

Most of our typewriters were manual Royals and Remingtons. There were a few electric models that Mr. Walton wanted all of us to practice on during the course of the year.

During my few sessions with the electrics, I found myself pushing the keys too hard due to being used to the manual keys that required effort. The result was a double or triple letter where just one was needed: “TThheee wwiinnntteerrr ooff oouuurr ddiiissccooonntteeenntt …”

Once Mr. Walton felt we were ready, he would set aside a few minutes at the end of each period for timed typing. We would type copy he had given us for five or so minutes then figure up our words per minute.

I wasn’t the best but I wasn’t the worst, either. I usually came out at between 40 and 50 words per minute.

In fact, Mr. Walton had us cut out photos of cars and stick them on a road course poster on the wall. My car was a Thunderbird and it ran basically in the middle of the pack at around the 45 WPM mark.

The gist of all this is simple: I finished the course with a useful skill that I was to put into practice three or four years later.

* * *

Dr. Joseph Morrison set me on a course that would change my life. He taught a course in feature writing that I took the fall of 1967.

Dr. Morrison had the same serious outlook that I had seen in Mr. Walton. The difference was that the college professor didn’t always restrain his criticism.

Under his tutelage, we were required to turn in a feature story each week based on our own interviews and research. Our copy had to be typed and single-spaced.

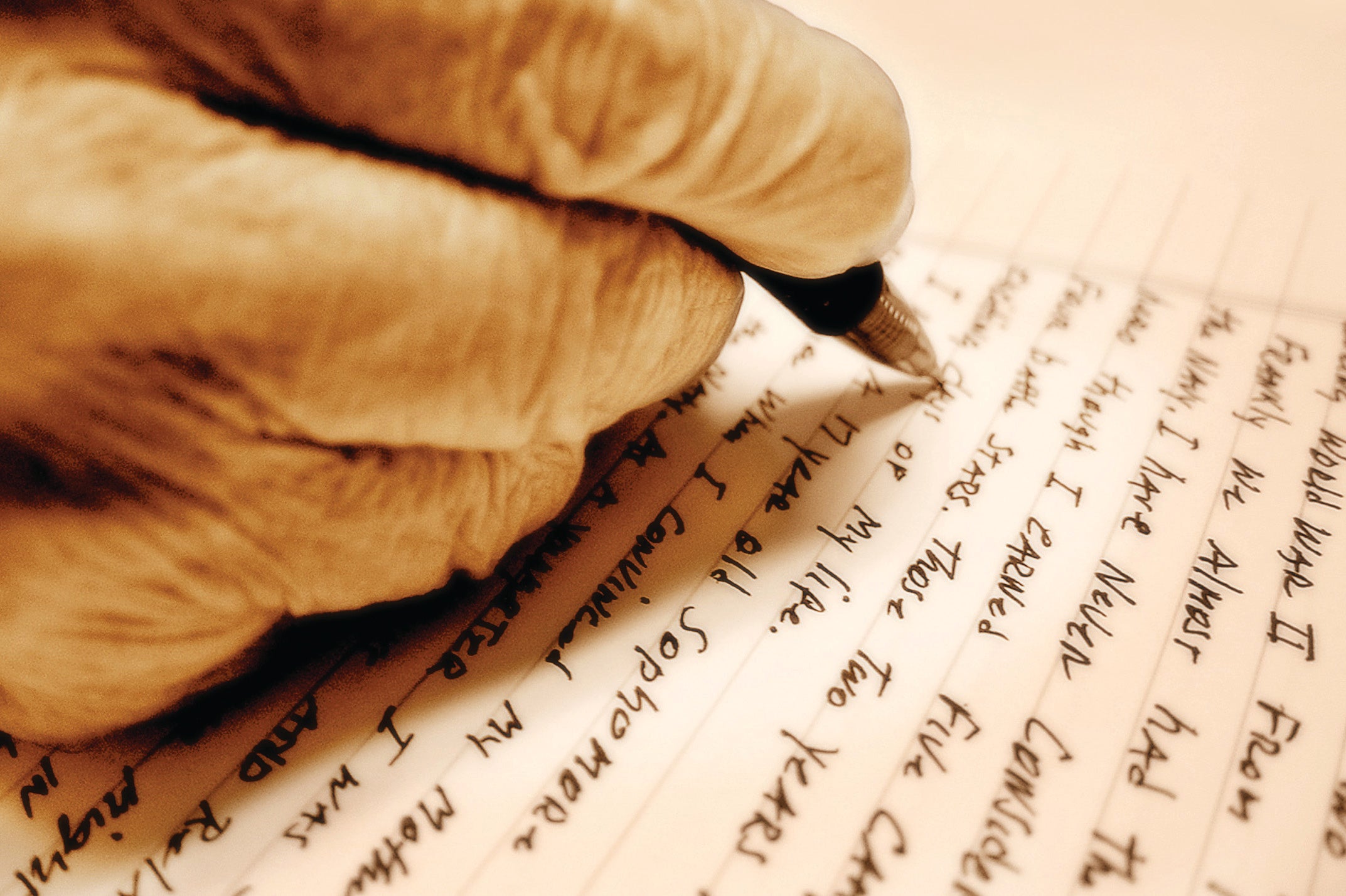

Using my interview notes, I would write my story by hand before typing it on coarse copy paper supplied by the university. Mistakes, fortunately, could be x’ed out, else I would have obliterated the school’s paper budget.

One week I had to borrow a typewriter from another student for my weekly feature story.

The font type was in script that looked like handwriting.

I dutifully turned in the copy. The next class Dr. Morrison handed out our graded stories. On the edge of my paper he had written that he had trouble reading my script font and for me to ditch the typewriter — or words to that effect.

In fear and trepidation, I got my old typewriter back.

What Dr. Morrison lacked in collegiality he made up for in the finer points of journalism. I entered his class as ignorant of newspaper writing as I had been of typing when I started Mr. Walton’s course.

By early 1968, I was able to both write a story and type it up within a reasonable amount of time. And I fulfilled the last assignment which was to get an article published. Mine appeared in The Courier-Tribune.

When Dr. Morrison’s class ended, he called me into his office. He told me I could be an average newspaper writer but gave me no illusions that there would be Pulitzers in my future.

I thanked him, having no idea that I would wind up being an actual newspaper reporter.

Now, after 36 years of writing for newspapers, I have to give credit to Mr. Walton and Dr. Morrison for helping me to a semblance of a career with the press.

And I say to all those who read my drivel — sorry about that.

Larry Penkava, who has written Now and Then since 1994, wouldn’t know what to do with a real job.